Corpus linguistics: fascinating beyond words!

We live in what has been dubbed the “Information Age”, and it would be hard to deny the name. Not only are we bombarded with outside information daily via internet, we also create information and, essentially, release it into the universe with everything we do. All this data is incredibly valuable in aggregate; the ever increasing processing power of computers allows us to identify infinite correlations and trends in the combined data floating through the ether. One merely needs to know how to collect and analyze it. “Big Data” is big business, and everyone is scrambling to discover new insights into a myriad of complex systems. Analysts use those insights to eke out a competitive advantage in every sphere of life, from identifying the most effective marketing strategy to identifying rare genetic disorders.

During my days as a lab tech, I used statistical analysis to look at changes in the number of mRNA transcripts – basically short, functional copies of active genes that the cell uses to make proteins – that mapped to different areas across the entire mouse genome in order to identify which genes’ expression increased and which decreased when embryonic cells developed into neurons. And while the analysis of transcript frequency in a sequencing dataset relates very directly to neuroscience, many people may be surprised that we can also use “Big Data” to identify neurological disease by looking at word frequency in a large bodies (corpora) of collected writings or transcribed speech. The study and statistical analysis of word frequency patterns in corpora is known as “corpus linguistics”, and it can encompass many disparate fields of interest from neuroscience to sociology. When it comes to the former, we’re talking about detecting the indirect effects of neurological changes in the brain as they’re expressed through language.

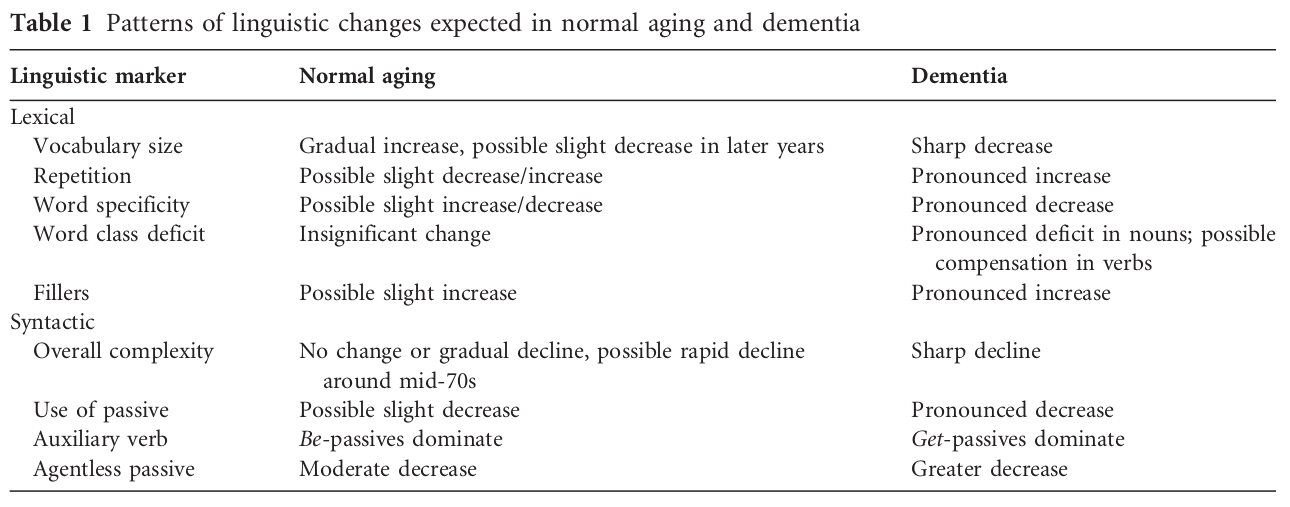

One neurodegenerative disease well known for causing marked changes in linguistic expression is dementia, and the most infamous form of dementia is Alzheimer’s Disease. Indeed, several studies have noted that the cognitive deterioration experienced by dementia patients leads to rapid vocabulary decline (especially with respect to less commonly used and more specific words), increased repetition and dysfluency – involuntary disruptions in the flow of speech. It’s no surprise, then, that there have been a number studies analyzing the complexity of both the written and spoken language of dementia patients. One group of researchers at the University of Toronto characterized the linguistic effects of both dementia and normal aging (see Table 1), and some studies suggest that lexical analysis could even be used as a tool for the early diagnosis of dementia.

Pretty cool, right? Let’s take things a step further and get a little analytical, ourselves! The press has reported extensively over the past two years about general suspicions that the current president of the United States, Donald Trump, may be suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Now, President Trump is not known for his eloquent speech, quite the opposite, and it is worth noting that his father suffered from the disease for six years prior to his death. Would it be possible to gain some insight into the President’s cognitive health by peeling back the face value of what he says and looking at the words, themselves? Thanks to his long-lived fame, there are several interview transcripts available for lexical analysis. There are also a number of tools available to parse the text, but I’ve used a web-based application called “Voyant Tools” to do a diachronic analysis of whether President Trump’s speech patterns have changed since the 1980s in a way that may be consistent with the onset of dementia.

Methods

I tracked down transcripts of the following six interviews online:

- An interview with Rona Barrett of the Washington Post, 1980

- A 1987 airing of the Larry King Show

- A partial transcript an Oprah Winfrey Show interview from 1988

- Another interview with Larry King on CNN from 2005

- Another Washington Post interview with Bob Woodward & Robert Costa from 2016

- Excerpts from a New York Times interview with Michael S. Schmidt in 2017

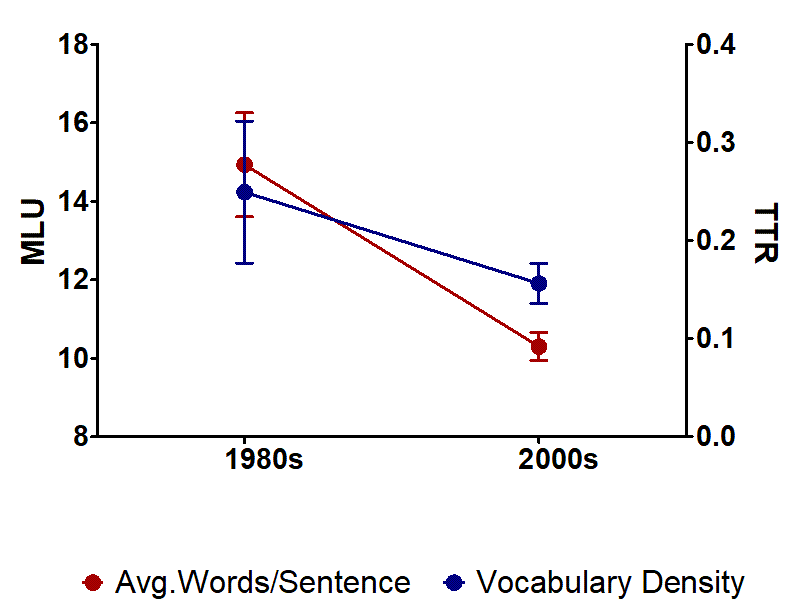

Interview transcripts contain a record of speech for all who participated, so I needed to clean up my data before processing by removing any text that did not represent an utterance made by Mr. Trump. I also removed the identity tags for each response and any insertions made by the transcriber, such as “inaudible” or “cross-talk”. I then uploaded the plain text files to Voyant Tools for analysis. To keep things simple I separated the interviews into two groups, one for the interviews of the 1980s and another for those of the 21st century. I looked at two metrics that correlate with language complexity: type to token ratio (TTR), which is simply the number of unique words divided by the total word count of the transcript and is used as a measure of lexical complexity (vocabulary density); and the mean length of utterance (MLU) – more simply, the average number of words per sentence, a measure of syntactic complexity. I took the data and ran them through GraphPad (statistical analysis & graphing software) to get the following figure.

Results

Looking at the graph, it’s plain to see that there is a marked downward trend for both metrics since the 1980s. While the 63% drop in vocabulary density is not statistically significant – the standard error for the earlier group is quite large – the trend is obvious. Additionally, our measure of syntactic complexity does indeed demonstrate a statistically significant decline of 69%. Now, this analysis isn’t perfect. I was limited to what transcripts (or parts of transcripts) I could find easily online, so the sample sizes are small and the data may be skewed by selective redactions from the incomplete transcripts. Furthermore, the later interviews are more politically-leaning than those done 20 to 30 years prior. While Donald Trump did consider running for Republican nomination in 1988, he never followed through. His first real foray into politics was in 2000, when he ran in and then subsequently dropped out of the nomination contest for the Reform Party. So, it is fair to speculate that some of the decline in vocabulary density could be due to the convergent political themes of the later interviews, whereas the diversity of topics covered in the interviews from the ‘80s is likely greater.

So, is Mr. Trump is experiencing the early stages of dementia? Unfortunately, we can’t draw any definitive conclusions from this mini-study. Although, we did obtain an interesting result that could warrant further investigation; it might prove more conclusive with a larger dataset and more sophisticated methodology. It’s also worth noting that a group of corpus linguists working in the cognitive field met in 2008 to promote critical discussion of methodological issues that have developed in the space where the fields of corpus linguistics and cognitive linguistics meet. They concluded that, “While cognitive corpus linguistics has developed a range of sophisticated analytical methods, the use of corpus data is also associated with a number of unresolved problems.” Most notably, they remarked that, “The lack of convergence between salience and text frequency challenges the ability of corpora to serve as a shortcut to cognition.” So, please keep in mind that when it comes to diagnosing neurological disease from afar, your mileage may vary.

Recommended Reading: If you found this post interesting, I recommend you read the UofT study. The researchers analyzed the collected writings of 3 British authors: Iris Murdoch, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s; Agatha Christie, who was suspected of suffering from the disease; and P.D. James, who aged normally. Their study looks at a wealth of lexical markers of dementia and goes into profound detail on this subject.